Darren Aronofsky’s psychological thriller Pi (1998) is notable for its use of puzzle and mind-game film storytelling techniques. The film follows protagonist Max Cohen (Sean Gullette), a mathematical genius and anxiety-ridden paranoiac, as he attempts to decipher a hidden pattern which underlies reality. Reflexively, his journey and the film’s structure itself take on the form of a pattern; a dynamic between chaos and order in the gaining of knowledge, and conflict with entities intent in exploiting this knowledge. This essay argues that Pi’s use of puzzle mind-game storytelling highlights issues surrounding authoritarian institutions, such as corporate capitalism and organised religion, and their attempts to exert power over the individual. This exercise is codified in the oscillation of Max’s psychological state from chaotic to orderly, and a continuous shifting between power and disempowerment. Also emergent in this analysis are issues of competing definitions of power and ideas of how it may be overcome.

Pi can be classified as a puzzle film for a number of reasons. Diverging from classical storytelling in the jarring immediacy of being shot on high-contrast, black and white reversal film, it disorients the viewer. Defined by Pisters (2012) as a ‘theorematic film’, Pi is portrayed from the outset as a problem to be solved. Max’s opening narration introduces us to a testable hypothesis; “Within the stock market there is a pattern as well. Right in front of me, hiding behind the numbers.” (Pi, 1998). Fostering a sense of instability, the nature of reality is put into question, making the viewer aware they are embarking upon an endeavour of uncertainty. This is in keeping with one of Buckland’s (2009) defining features of the puzzle film, of placing the viewer in the position of figuring out the rules of the narration. While characterised as a pleasurable experience, its nature in Pi is strikingly unpleasant, evidence of the film’s success in enabling the viewer to share the distressing experiences of the protagonist.

With its emphasis on the intellect, reason and pathological mental states, Pi can equally be defined as a mind-game film. Through the privileged placement of the protagonist’s point of view, a highly intersubjective experience is created, and becomes a key focal point in which “conundrums of relations between body, brain and consciousness” (Elsaesser, 2009, p.18) are explored. We feel Max’s moments of frustration, suspense, and epiphany. We are crammed inside the experience of his frequent migraines, hallucinations and paranoia through a conjunction of camera angles, editing and non-diegetic sound. This builds a techno-kinetic structure commonly found in the cinema of the body (Laine, 2007), and intensifies the subjective experience. Laine argues that as Max goes through a migraine, so does the film itself. This is notably reflective of the film’s psychophysiological persona, and its recurring themes of the human relationship to technology.

Max’s interactions with other characters in the film represent relationships of power between the individual, and authoritarian institutions. This relationship is not static nor unidirectional, as the film moves through expressions of both the losing and gaining of power by Max and the institutional entities he encounters. Marcy Dawson, partner of a predictive strategy firm which is interested in Max’s research, embodies a deeply authoritarian system of corporate capitalism. She is relentlessly harassing and imposing upon Max in her attempts to garner information from him. There is a sense of Max having little control as he becomes increasingly distressed and paranoid.

In one scene, Max is chased by Marcy (Pamela Hart) and her cronies. When caught, Marcy exerts physical violence on him and her friend draws a gun. Up until this point, only Max had been portrayed as mentally unstable, but now it is Marcy who embodies madness. Her sudden, frenzied reaction effectually shifts disempowerment onto her as she exposes her anxieties about the stock market crashing, revealing her fear of the loss of control. She epitomises the corporate obsession with production, shouting, “I don’t give a shit about you, I only care about what’s in your fuckin’ head! […] It’s survival of the fittest, Max, and we got the fuckin’ gun!” (Pi, op. cit.). These portrayals of madness do not speak to the madness of the characters themselves, but of the “capitalist system which they embody”, with Max’s mental instability an inevitable response to persecution under said system (Harper, 2009, p.6). This implies that madness is embodied by both the perpetrators and the victims, indicating that the line between power and disempowerment within such a system is blurred. This reiterates the presence of a powered dynamic. Although Marcy holds power over Max physically, he holds power over her in having knowledge that she is desperate to possess.

This power in knowledge extends further. Through a series of puzzling coincidences, Max meets Hasidic Jew Lenny Meyer (Ben Shenkman). Lenny uses an appeal to Jewish identity when learning Max’s surname, and encourages him to take part in a binding ritual. This is reflective of the coercive attempts of religious organisations to gain followers based on a shared sense of collective identity. Despite Max’s initial resistance, Lenny eventually strikes his interest in the Torah by stating that an important, divine pattern may exist within its numerical framework. In the chase scene with Marcy, Lenny and his friends rescue Max. Like Marcy, they assert physical violence over him, while simultaneously revealing fears over his sharing of knowledge. Lenny’s desperation to use Max’s knowledge is reflective of a powered dynamic in the distinction between individual spiritual experience, and the attempts of institutionalised religion to control it. Broze & Vibes relate this to the relationship between the individual and the authority of the State as a whole, arguing:

Anarchy is to Statism, as Spirituality is to Religion. Anarchy is the physical manifestation of freedom and spirituality is a mental manifestation of freedom. In contrast, Statism is control in the physical sense, and religion is control in the mental or spiritual sense. (Broze & Vibes, 2015, p.6)

Max’s own control over his mental state shifts precariously throughout the film, underlying these interactions, and relating directly to his level of knowledge. His mentor, Sol (Mark Margolis), attempts to dissuade him by reiterating that the world is irreducible and chaotic in nature. Max responds with a conviction that there is an order, and a determination to find it. This is immediately interrupted by hallucinatory sequences which trigger disorientation and breakdown. Woods (2012) views these breakdowns as the hyper-extension of mathematical processes. Drawing from Sass’s view of madness as an intensified enhancement of reason, and alienation from the emotions, instincts and the body (Sass, 1992, cited in Woods, 2012), Woods notes Max’s body as the key site for the expression of his pathology. An abrasive, synthetic sound effect directs us to Max’s physical pain when his breakdowns and migraines begin. Conversely, however, these breakdowns are followed by periods of epiphany, and a sense of his gaining knowledge and understanding. A more upbeat use of soundtrack signifies moments of mental stability. This contrast between painful, chaotic disorientation and high-energy determination expresses a pattern within the film’s structure itself, and further conveys a dynamic of power which is continually in flux.

As Max works at his computer, getting closer to deciphering the code, he begins to hear his next-door neighbour having sex. We have previously been given clues towards his sexual attraction to, and his intense social awkwardness around her, an indication of his lack of sexual prowess. Hearing this, Max becomes visibly distressed, and suspense builds as he begins to break down. During this, he notices a growth on his head, an example of the somatic representation of pathologies, and their leaving of traces on the body (Deleuze, 1992, cited in Elsaesser, 2009). As his migraine peaks, Max violently penetrates the growth with a subcutaneous injection device while his neighbour simultaneously reaches orgasm, symbolising his desire to penetrate her, and his inability to. Everything stills, and Max’s computer spits out a number which is the key to unlocking the code. He begins to write it down, before realising the knowledge is already in his head. There is a flash of white light, and in the next shot we see him passed out with a nose bleed.

It is unexplained if the white light denotes an enlightenment experience, but some attainment of knowledge has occurred, as he is thereafter able to predict stock picks directly from his head. The crash could be interpreted under Elsaesser’s (op. cit.) description of productive pathologies, serving to disorient and disassociate the character, and triggering a rebooting of consciousness. Max’s periods of disorientation are always followed by a reorientation in which he gains deeper knowledge. Despite the simultaneous disempowerment of his computer and his mind, the result is ultimately a regaining of power.

Cyclically, then, Max’s performance of relentless order-seeking is expressed in paranoid chaos, which leads in turn to further seeking of order. This puts into question the very distinction between chaos and order itself, alongside the dichotomy of sane and insane. When Sol says “this is insanity, Max!”, Max responds by asking, “but what if it’s genius?” (Pi, op. cit.). Elsaesser (op. cit.) defines this as a common mind-game theme in which the distinction between the two concepts is suspended. The assumption of power is thus stripped from the two, and both protagonist and viewer are disempowered as they attempt to find the answer. The ambivalent representation of Max’s mental state exacerbates this, not only by making him unreliable as narrator, but by creating a sense of dubiousness about which points of view are ‘normal’, ‘real’, or around any answer he may be shown to have discovered.

As Max shares his knowledge with Marcy, often under duress, his mental state destabilises, described by Kelly (2006) as an erosion of individual agency. This transaction of knowledge sharing is thus performed under “threat of punishment, injury, imprisonment, destruction”, as opposed to that of a voluntary transaction, making it one of political power rather than economic power (Rand, 1986, p.47). The distinction here is important, as it highlights the difference between corporate, state-sanctioned capitalism, and a genuinely free market system, alluded to by Max himself as a ‘natural organism’ (Pi, op. cit.). Rather than the personification of ‘capitalism’, Marcy and her goons, in their brutish attempts to manipulate the market, aptly represent the process of corporate collusion with authoritarian power. Her desire to control the market with Max’s knowledge is an attempt to override spontaneous order, and in her loss of stability we are shown that her power, and the power of the forces she represents, lies only in her ability to use coercive force against others.

Conversely, Max’s compliance with the entities that exert power over him could be seen as reflective of the concept of ‘subjectivation’, in which the subject is always part of and compliant with the conditions of the world, and the ‘technologies of power’ which seek to control (Foucault, 1988). This view rejects the idea that power is held only in the exertion of physical force, and is instead perpetuated by, and intrinsically bound up in, the theoretical and practical knowledge structures of society. This seems to leave little room for free will and individual agency. However, Foucault also conceptualised a more self-affirming process of ‘subjectification’ and the ‘technologies of the self’ (Foucault, ibid.) and has asserted that “where there is power, there is resistance.” (Foucault, 1990). He recognised a potential for positivity in power relations, stating:

We must cease once and for all to describe the effects of power in negative terms: it ‘excludes’, it ‘represses’, it ‘censors’, it ‘abstracts’, it ‘masks’, it ‘conceals’. In fact power produces; it produces reality; it produces domains of objects and rituals of truth. The individual and the knowledge that may be gained of him belong to this production. (Foucault 1991: 194)

Max’s belief that nature can be defined in numbers, and his attempt to understand it through the hyper-extension of reason, might be viewed as exemplary of his entrapment in the system of subjectivation, with the fragmentation of his psyche an inevitable result. Pi’s director, Darren Aronofsky, shares his intent with the portrayal of Max’s dissolution of self in the following:

I think we’re meant to know everything, it’s just a matter of when and how. I think this knowledge of God precludes the existence of the ego and the self and that as Max gets closer and closer to finding this universal order, his own self starts to disappear more and more. That’s the underlying conflict of the movie. (Holmberg, 2014)

Individualist anarchist thinkers, however, have viewed this idea of an unchanging, transcendent ego as merely another form of self-oppression, stating that only in cultivation of egoism, and ‘the-finite ego’ can there be true means of liberation from external power (Stirner, 1915, cited in Antliff, 2007). There is a distinction between revolution and insurrection, the former being merely a changing of who has power, and the latter being the assertion of egoism over power in an anarchic way of being (Antliff, 2007). Perhaps it is for this reason that Max goes through a repetitive flux of power and disempowerment, and it is only through performing his own act of insurrection that he becomes truly free.

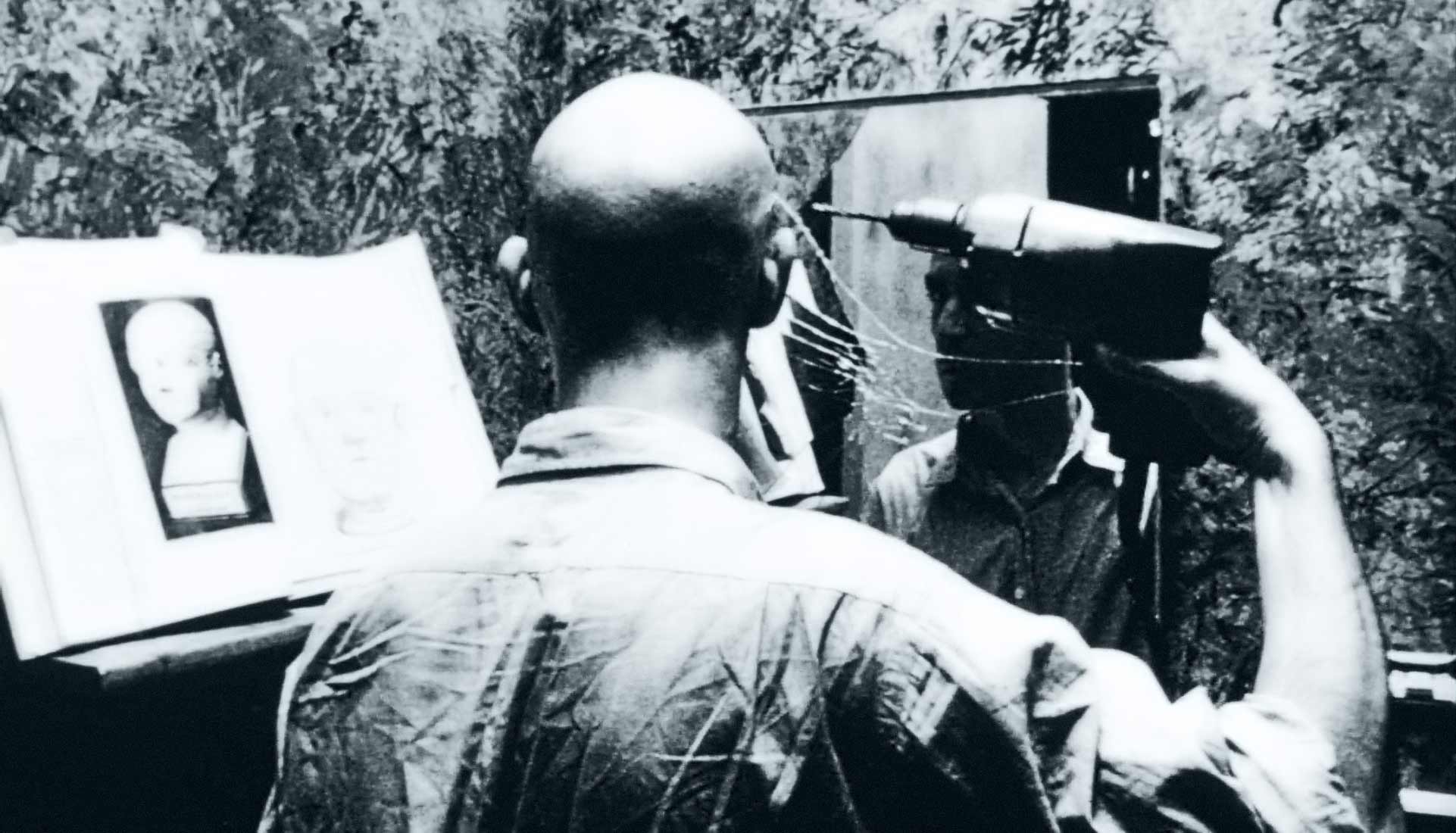

As the film draws to a close, Max begins to tear down his computers while screaming the numerical code. Looking at his reflection, he holds a piece of paper with the code, and sets alight to it. We hear one final recitation of the story that he has narrated several times, his story of staring into the sun as a child, “When I was a little kid, my mother told me not to stare into the sun. So once when I was six I did” (Pi, op. cit.). He takes a drill, and inserts it into the growth on his head. Following this, he can no longer do maths mentally, yet he seems content. In this violent act of self-liberation, Max regains his personal freedom by destroying the source of his knowledge, and ultimately of his pain. The replaying of his story of childhood defiance and antinomianism adds strength to this. The image of drilling his own skull is phallic and penetrative, placing this scene into the realm of a mindfuck. He is, in effect, fucking his own mind, yet it is liberating, and for the first time he appears to be acting with clear intention and without neuroses. This symbolises the positive, productive and freeing aspect of masculine energy, rather than the tyrannical aspect seen in earlier scenes which show him penetrating a hallucinatory image of his brain with a pen. Woods (op. cit.) describes this as the transferring of the site of mental breakdown to the site of cure.

Max ultimately gives up his endeavour to understand reality through reason. No matter how close he gets to objective understanding, even when he appears to have reached it fully, he chooses to destroy it within himself. This is an act of subjectification. Rather than transiently gaining power, he becomes free, and echoes, profoundly, the following by Stirner:

‘Absolute thinking’ is that thinking which forgets that it is my thinking, that I think, and that it exists only through me. But I, as I, swallow up again what is mine, am its master; it is only my opinion, which I can at any moment change, i.e.; annihilate, take back into myself, and consume. (Stirner, 1915:453).

To conclude, Pi uses puzzle film and mind-game storytelling to convey a dynamic pattern of shifting power relations not only in its practical film-making processes, but also in its portrayal of character interaction, the protagonist’s internal state, and within the film’s narrative structure itself. Its diegesis of one man’s attempt to know the nature of reality reflexively refers back to the non-diegetic aspect of the film’s philosophical bent, and its lack of ontological conclusivity. Max’s level of power throughout Pi is largely tied up in his level of knowledge, reflecting the Foucaultian world-view of the connection between power and knowledge. However, the presumption that power is inextricable from knowledge is challenged by Max’s final act of destruction of the source of his knowledge, resulting in his self-liberation. This illuminates the multifaceted manifestation of ‘power’, which itself involves a dynamism; it can be both positive and negative, productive and destructive, voluntary and coerced. Finally, the representation of corporate capitalism and organised religion, in their confrontations with Max as an individual entity, reveals an unstable and fluctuating distribution of power relations within society. This, ultimately, epitomises the struggle of the individual for social, economic, psychological and spiritual liberty.

Bibliography

Antliff, A. (2007) Anarchy, power, and poststructuralism. SubStance, 36(2), pp.56-66.

Broze, D. & Vibes, J. (2015) The Conscious Resistance: Reflections on Anarchy and Spirituality. Poland: Amazon Fulfillment.

Buckland, W. ed. (2009) Puzzle films: complex storytelling in contemporary cinema. Chichester: Wiley‐Blackwell.

Elsaesser, T. (2009) ‘The Mind Game Film’, in Buckland, W. (ed.) Puzzle Films: Complex Storytelling in Contemporary Cinema. Chichester: Wiley‐Blackwell.

Foucault, M. (1988). Technologies of the Self. In Martin, L., Gutman, H. & Hutton, P. (Eds.)

Technologies of the Self: A seminar with Michel Foucault. pp. 16-49. Amherst: The University of Massachusetts Press.

Foucault, M., 1990. The history of sexuality: An introduction, volume I. New York: Vintage.

Foucault, M. (1991). Discipline and Punish: the birth of a prison. London: Penguin.

Harper, S. (2009) Madness, power and the media: Class, gender and race in popular representations of mental distress. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

Holmberg, E. (2014) Noah – Part 1: Eternity in Darren Aronofsky’s Heart. [online] Available at: https://theapologeticsgroup.com/noah-part-1-eternity-in-darren-aronofskys-heart/ [27/03/2018]

Kelly, B.D. (2006) The power gap: Freedom, power and mental illness. Social Science & Medicine, 63(8), pp.2118-2128.

Laine, T. (2015) Bodies in Pain: Emotion and the Cinema of Darren Aronofsky. New York/Oxford: Berghahn Books.

Pi, 1998 [film]. Directed by Darren Aronofsky. USA: Protozoa Pictures

Pisters, P. (2012) The Neuro-Image: A Deleuzian Film-Philosophy of Digital Screen Culture. Stanford University Press.

Rand, A., Branden, N., Greenspan, A. and Hessen, R. (1986) Capitalism: The unknown ideal. New York: Penguin.

Stirner, M. (1995) Stirner: the ego and its own. Cambridge university press.

Woods, A. (2012) ‘Mathematics, masculinity, madness.’ Madness in context: historical, poetic and artistic narratives. Oxford: Interdisciplinary Press.