Read Part I: Shells, Ghosts & The God Left Out of the Machine: A Literature Review.

Abstract

Ghost in the Shell (1995) has often been interpreted under dualistic terms; an example of cyberpunk’s perpetuation of the Cartesian separation between mind and matter. When examining the transhumanist ideology underlying the film, however, a more esoteric form of dualism emerges, indicating something significantly more interesting than a mere regurgitation of Cartesianism. In line with claims that the philosophical basis of transhumanism consists in a religious sub-structure, which critics have named a modern-day ‘techno-Gnosticism’, religious imagery and motifs are evident within the film. The claim that Gnosticism underlies transhumanism is supported by the presence of Gnostic philosophy within Ghost in the Shell and its engagement with transhumanist themes, and additionally by demonstrating that other philosophical paradigms accredited to transhumanism, and to Japanese animé in general, are insufficient for explaining the existential and spiritual anxieties the film represents.

Mamoru Oshii’s Ghost in the Shell (1995) – hereafter referred to as Ghost – is considered a benchmark of cyberpunk animé and has been noted for its exploration of technological themes in a philosophical light (Matthews, 2005). Set in 2029 in the fictional Japanese New Port City, Ghost exhibits debates about the relationship between mind and body tackled historically in philosophical thought, a common trope in cyberpunk’s grappling with transhumanist themes (Jacobs, 2018). The central philosophical question in Ghost deals with anxiety and ambiguity about what it means to be human in a transhumanist world.

Setting the Stage

Transhumanism, summarised as the liberation of the human race from its biological limitations, is considered a system of thought emerging from advancing technologies and contemporary biomedicine (Fukuyama, 2004). Others, however, have traced reflections of transhumanist thought as far back as the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh c. 1700 BC and as such, visions of a transforming human species have been argued “as ancient as the species itself” (Bostrom, 2005. p.1). Self-transformation through technology has been viewed as simply the nature of our cognitive machinery, the result of us being “natural born cyborgs” (Clark 2003, cited in Haney, 2006). The core philosophy of transhumanism emphasises humanity’s evolutionary trajectory along technological lines, in order to “reshape our own nature in ways we deem desirable and valuable” (Kraftchick p51).

Bostrom (op cit.) argues that transhumanism has its roots in rational humanism, emphasising a standard of empirical science and critical reason. Further, an indication of the transhuman should include an “absence of religious belief” (Esfandiary, 1989 cited in Bostrom, op cit.). It is notable, then, that cyberpunk texts often contain religious themes (Bitarello, 2018), and Ghost is no exception. Although taking place within a setting of scientific materialism, the film simultaneously contains religious imagery and Biblical verses, standing at odds with its technological setting. Matsamune Shirow, creator of the original Ghost in the Shell manga (1991- 1996) believes that despite not doing so consciously, his work reflects a convergence of “sci-tech and religion” present within human perception (Schodt, 1998). Transhumanist ideology has in turn been argued as containing an underlying religious philosophy (Pugh, 2017). Thus, the presence of religious themes within Ghost and its engagement with transhumanism should not be assumed coincidental, and the claim that transhumanism operates within a wholly secular and scientific framework should be critically examined.

While the ‘mythology’ within cyberpunk of viewing the mind as a pure, immaterial substance has been accused by McCarron (1995) and Holland (1995) as being specifically Cartesian, an older dualism actually underlies Ghost’s philosophical inequities. Themes from ancient Gnosticism, and particularly strong parallels to the myth of Sophia taken from the Nag Hammadi texts c. 400 AD can be identified within Ghost. This investigation will thus provide a first foray into Gnosticism within Ghost, arguing that this particular religious dualism constitutes the true philosophy underlying both the film and the roots of the transhumanist movement. Opposing philosophical contexts surrounding the film will be outlined before re-imagining the character of Motoko Kusanagi as the Gnostic Sophia, following the stages of her mythic fall and redemption. Finally, in line with Irving’s (2006) claim that Gnosticism operates on a mechanism of reversals, primarily of Christianity, it will be shown that the Biblical scripture present in the film is subverted in such a way which allows for it to fit within a Gnostic narrative, offering further evidence of this pervasive ideology.

The Move Towards the Transhuman & Non-Duality

Ghost portrays a world of human advancement analogous to that envisioned by proponents of transhumanism. Futurist Ray Kurtzweil in his work The Singularity is Near (2010) discusses the replication of the brain’s neocortex and the potential to ‘upload’ the human subject to superior thinking machines. Kurzweil coined the term ‘singularity’ to describe this process ending with the human merging with the machine. Dmitry Ishtov, founder of the 2045 Initiative life extension project, professes goals of transferring the individual personality to a cybernetic carrier or ‘avatar’ and extending life “including to the point of immortality” by the year 2045 (Kraftchick, op cit. p.49). Hans Moravec (1988) maintains that machines can become repositories for human consciousness, and thus, can become human beings. In other words, “[y]ou are the cyborg, and the cyborg is you” (Hayles, 2008 p. xii).

In Ghost, the human subject or individual personality, called a ‘ghost’ and sometimes referred to synonymously with ‘soul’, can be uploaded into an entirely artificial, cybernetic body. The main protagonist, Major Motoko Kusanagi, Public Security Section 9 government agent, is a human ghost residing within one of these carriers. The film oscillates between her attempts to hunt down a mysterious hacker known as the Puppet Master and her inner, existential crisis pronounced by her condition of being a cyborg. The presence of the cyborg in cyberpunk serves to “interrogate the limits of humanity” (McCarron, op cit.) and break down boundaries of human and machine in the mind of the viewer (Puntillo, 2014). Authors have accordingly applauded cyberpunk’s capability to deconstruct dualistic oppositions (Pyle, 2001).

Transhumanist proponents similarly advocate for a mutual co-constitution between the terms ‘human being’ and ‘technology’. As Clark’s (op cit.) ‘natural born cyborgs’, technology is just another part of us, and not merely a tool that we use (Kraftchick, op cit.). In Ghost, Kusanagi reiterates that when “man realises technology is within reach, he achieves it. Like it’s damn near instinctive” (Ghost, 1995). Donna Haraway, in her widely cited Cyborg Manifesto (2006) asserts that liberation from cultural oppression can be achieved by destroying duality through the liminal transformation of machine-organism symbiosis.

If conceding the transhumanist position that a non-dualistic framework for defining the human-machine relationship is favourable, we must ask why Kusanagi experiences such high levels of anxiety about her human identity. If we are indeed natural born cyborgs, then there should be no need to differentiate between the human soul and that of the machine. Yet, the artificiality of Kusanagi’s body appears to challenge the stability of her selfhood, a lack of mind-body entanglement offering no tangible basis for the knowledge that her ghost was ever really human. When the Puppet Master assembles and hacks into a cybernetic body resembling her own, and leaves traces of a ghost within its cyber-brain, she is forced to ask: “[w]hat if a cyber-brain could possibly generate a soul all by itself? And if it did, just what would be the importance of being human then?” (Ghost, op cit.). The transhumanist presumption that humans can be seamlessly integrated with machines is, on the surface, formed of conflicting philosophical assumptions. It is Ghost’s engagement with these assumptions, and the implications of technological advancement advocated under transhumanism, which forms the basis for Kusanagi’s anxiety. To understand why she continues to question her personhood in a world where it is assumed that “we are cyborgs” (Haraway, op cit. p. 292), we must draw attention to these conflicting, outer assumptions, and in so doing discern the true philosophical ideology underlying Ghost and the move towards the transhuman.

The God Left Out of the Machine: Materialism or Informational Dualism?

William Barrett in The Death of the Soul (1986) maintains that the de facto philosophy of the Modern Age, permeating all schools of philosophy, the physical sciences and technological development, is that known as ‘scientific materialism’ (Barrett, ibid. p.7). The advent of mechanistic science in the seventeenth century was soon followed by an ideology of mechanism. In its assertion that “[m]an is a machine” (Barrett, ibid. p.xv) the idea of the human soul seemed “ghostly [and] insubstantial” (Barrett, ibid. p.57) with the mind being reduced to the passive plaything of material forces. Human consciousness was seen as merely epiphenomenal, a by-product of the brain. The notion of a human substance had left the forefront, and the following centuries saw this culminating in the ‘death of the soul’ – the denial of a substantial self or ‘desubstantialisation’ within philosophy (Barrett, ibid p.113) alongside the ‘death of God’ – the destruction of anything performing a religious function, or postulating a “true world” (Young, 2003).

Ghost’s outward setting is certainly one in which notions of God, religion and spirituality are no longer at the forefront. The word ‘soul’ is referred to synonymously with ‘ghost’, and although this has spiritual connotations, ghosts are reduced to a collection of memories. The Puppet Master’s ability to ‘ghost-hack’ individuals and implant false memories comes with the implication that stripping a ghost of its memories simultaneously strips it of its identity, equating the soul with memory itself. Kusanagi’s partner Batou explains: “[t]hat’s all it is, information. Even a simulated experience or a dream is simultaneous reality and fantasy. Any way you look at it, all the information a person accumulates in a lifetime is just a drop in the bucket” (Ghost, op cit.). The Puppet Master similarly reduces the individual to an accumulation of memory structures when he defines man as “an individual only because of his intangible memory” (Ghost, op cit.).

However, following with the acknowledgement that “memory cannot be defined, but it defines mankind” (Ghost, op cit.), the Puppet Master’s presentation of information as the basis of life takes on a flimsy, ethereal quality. When explaining that he is a sentient consciousness that has never possessed a body, he asks “can you offer me proof of your existence? How can you, when neither modern science nor philosophy can explain what life is?” (Ghost, op cit.). Katherine Hayles, in her seminal work How We Became Posthuman (2008) defines information within transhumanism as a “kind of bodiless fluid that could flow between different substrates without loss of meaning or form” (Hayles, ibid. p.xi). This definition emerged with the erasure of embodiment in the push to develop the thinking machine, and an assumption that informational patterns are privileged over material instantiation. As in Ghost, human identity can thus be viewed as an informational pattern rather than that which enacts embodiment. The reductionist view of memory as identity put forward in Ghost, based within a scientific, mechanistic world-view, contradictorily relies upon a dualistic framework which privileges ‘pure’ information. This has been recognised as a common result of cyberpunk’s engagement with Cartesian dualism, with McCarron maintaining that the genre’s goal is to achieve ‘pure mind’, necessitating the “Puritanical [sic] dismissal of the body” (McCarron, op cit. p.262).

Ambiguous Animism

Conflicts between this sort of dualism and Eastern animistic world-views have been touted as the source of ambivalence towards technology within Japanese animé. With Western views tending to separate things out, they clash with the holistic picture offered by animism (Matthews, op cit.) that non-human subjects and inanimate objects possess souls (Kitano, 2007) and can be assigned personhood (Richardson, 2016). Despite the enhanced need for technological advancement following the trauma and cultural despair of World War II, animism is argued to still significantly influence Japanese culture (Kitano, op cit.). Shirow has stated that his work ties most closely with animistic religious philosophy (Schodt, op cit.).

It follows, then, that this cultural conflict is the source of Kusanagi’s anxiety about her identity; an unnecessary crisis brought about by separating herself out. This is not entirely convincing. Authors have made assertions about such conflicts while implying a preference for animism as the more desirable world-view (Brazal, 2014), similarly reflected in the transhumanist attempts to destroy distinctions between human and machine. Western influence is often blamed for any ambiguity (Matthews, op cit.) and animism itself is never analysed as a potential source of philosophical uncertainty. In the context of Ghost, however, animism does not offer a suitable framework for the practicality of ‘mind uploading’, as it views the soul and its material counterpart non-dualistically, and thus inseparable. Moreover, even if attempting to read Ghost as an animistic allegory through which a human-machine hybrid gains spiritual realisation, Kusanagi’s transformation to something distinct from her previous self at the end of the film contests this, as it implies something lacking in her initial constitution.

To reiterate earlier conclusions, the transhumanist paradigm in Ghost necessarily requires a dualistic, not an animistic premise in order to allow for conceptions of mind uploading and transformation. It is the present author’s contention that Kusanagi’s anxieties are not simply the result of a conflict between animism and Cartesianism, but are instead the result of reformulations to the human being posed by moves towards the transhumanist singularity. Furthermore, in an attempt to quell Kusanagi’s anxiety, consciously or unconsciously, Ghost resorts to motifs from Gnosticism, a deeper and more ancient form of religious dualism which lies at the heart of the transhumanist ideology Ghost ultimately represents.

Gnosis Outside the Shell

Dubbing transhumanism a form of ‘techno-Gnosticism’, Pugh (op cit.) urges us to understand it in religious terms, calling it the reappearance of Gnostic philosophy in contemporary society. ‘Gnosticism’ is a modern term for spiritual world-views based upon early alternative accounts of Christianity. These come primarily from the Nag Hammadi texts, discovered in 1945 but dated to approximately the fourth century AD, holding some parallels with Jewish mysticism (Brazal, op cit.) and pre-Christian myth (Conner, 2016). Gnostic theology considers us as having fallen from the Divine, becoming trapped as spiritual fragments in a material prison (Tibaldeo, 2012). Sharing its philosophical origins with alchemy (Gilbert, 1987) Gnosticism mirrors transhumanism’s evolutionarily contextualised goals, with the alchemical process described as a form of “consciously assisted evolution” (Bartlett, 2009). Similarities between Gnosticism and transhumanist proposals for human enhancement have likewise been noted by Coeklebergh (2010) and Irving (op cit.), who describes it as “one of the most pervasive and influential mythological ideologies in our global society today”.

In the context of analysing Ghost’s engagement with an impending transhumanist world, then, it is of fundamental importance to identify any Gnostic themes within the film. From the outset, the very name ‘Ghost in the Shell’ connotes a dichotomy between spirit and matter, with the indication of an immaterial ghost confined to a material shell. Kusanagi, when reflecting upon her identity, reiterates this sense of feeling “confined, only free to expand [her]self within boundaries” (Ghost, op cit.). Gnosticism also emphasises the need for self-reflection, centred on the myth of the goddess or ‘aeon’ Sophia, from the Greek Σοφíα meaning ‘wisdom’. Sophia is essentially synonymous with the soul, or ‘world soul’ (Gaia, 2015). Her myth encompasses a fall from the immaterial pleroma into the world of matter, and her subsequent salvation. Conner (2014) describes Sophia as the “dangerous nexus between the spiritual and the material”, possessing similar boundary-bashing attributes as the transhumanist cyborg. Kusanagi’s character, pivoted on the reflection of her human soul and identity, can thus be read as story of transcendence and redemption to uncover threads of Gnostic philosophy within Ghost.

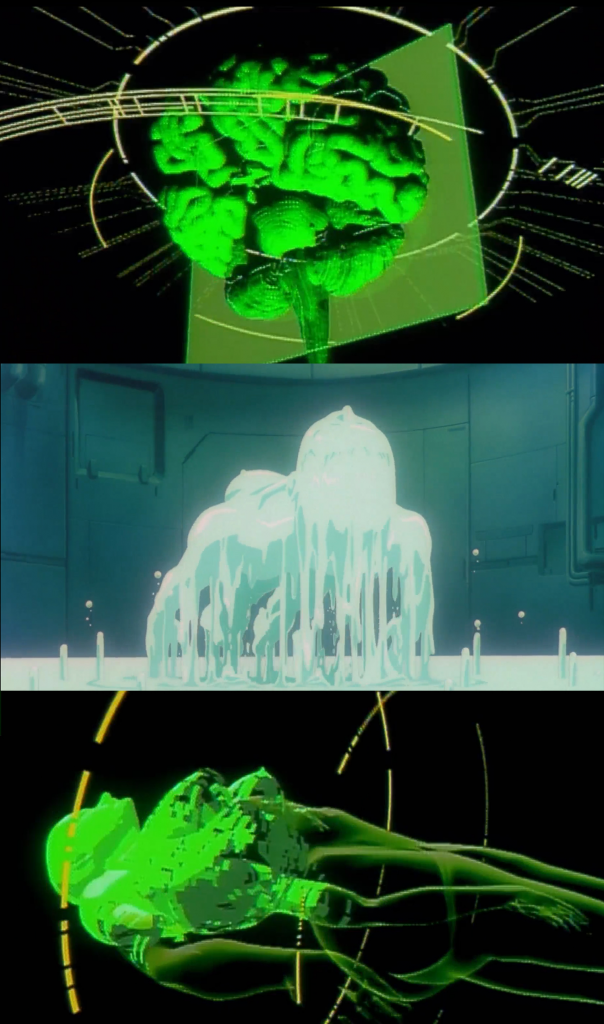

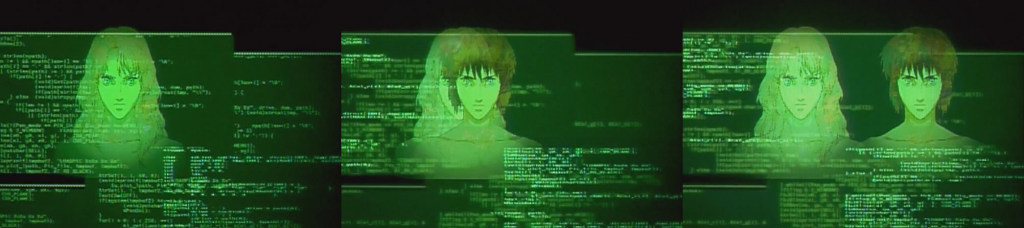

The film’s lavish opening credits sequence presents a richly detailed and intimate construction of Kusanagi’s body (figure 1). This entirely non-natural ‘birth’ sequence represents in technological language Sophia’s fall and emergence into the material world. With the credits appearing from encrypted text and images of her cybernetic brain being digitally generated, we get the sense of disembodied information being made physical, ‘made flesh’. Her dead expression as she looks at the cityscape beneath her window gives a sense of disconnect with the material world. Juxtaposed with this disconnect, however, is a secondary sense of submersion, with her body becoming absorbed in the environment around her as she activates her thermoptic camoflage (figure 2). This implies not only that her prison confines her ghost within a cybernetic body, but that it equally extends across the physical environment as well.

Mirror Symbolism, Gnostic Christ & Kusanagi’s Gnosis

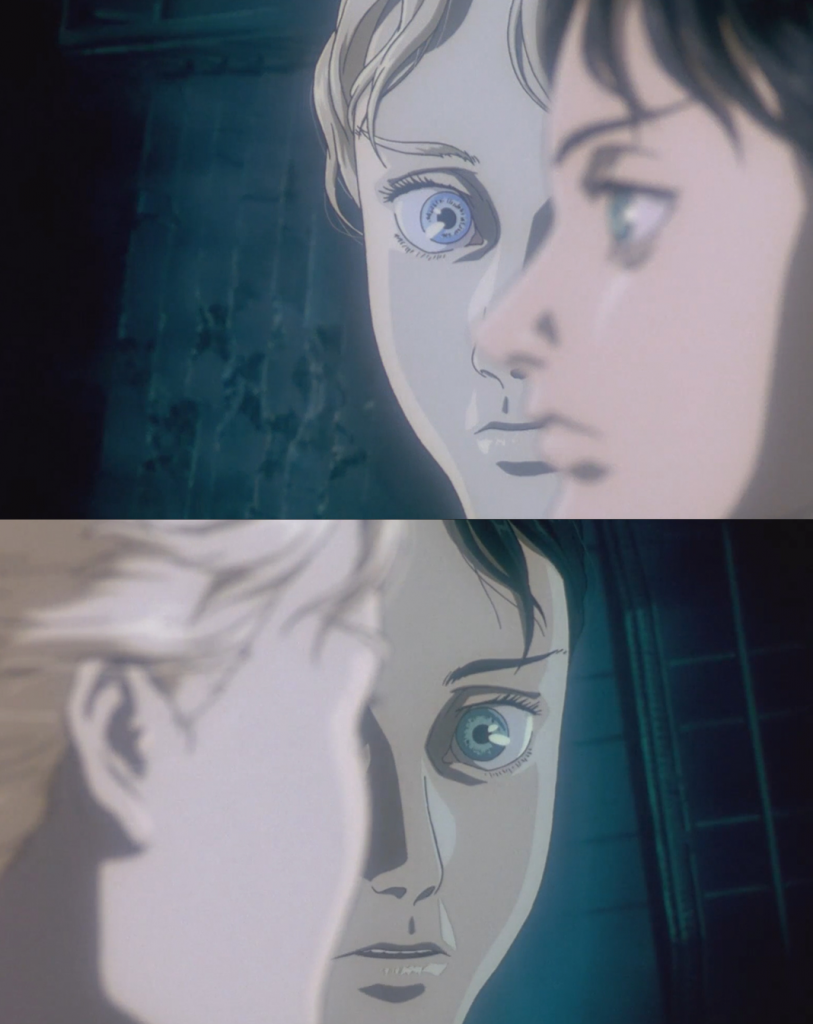

Recurring instances of reflective surfaces within Ghost denote the Gnostic philosophy of introspection, such as when Kusanagi sees a second version of herself looking back towards her through a window (figure 3). Sequences of rainfall and reflective water imagery commonly occur during pacing changes in the film. Perhaps the most notable of these shows the transition to an ambient sequence of Kusanagi deep-sea diving (figure 4) before a discussion with Batou about the constitution of herself as an individual. She shares her feeling of “becoming someone else” (Ghost, op cit.) as she floats to the surface of the water. Her voice is then heard by both of them, although she appears to have no control over it. The voice, seemingly projected from elsewhere, recites a passage from 1 Corinthians 13:12: “What we see now, is like a dim image in a mirror. Then we shall see, face to face”(The New Testament, cited in Ghost, op cit.). The significance of this Biblical passage will be discussed later.

Mirror symbolism is also present in Kusanagi’s relationship to the Puppet Master, as he takes on aspects of the Gnostic Jesus Christ. The Gnostics saw Christ as the divine syzygy of Sophia; her twin, consort or bridegroom (Parrott, 1977). The following from the Pistis Sophia relays: “Son of Man consented with Sophia, his consort, and revealed a great androgynous light. Its male name is designated ‘Saviour, begetter of all things’. Its female name is designated ‘All-begettress Sophia’.” (Mead, 2019).

Kusanagi’s lack of her own sense of self becomes swiftly characterised by an urgency to understand the Puppet Master, as though this will lead to a greater understanding of herself. Following a drawn out sequence of her body being torn apart and destroyed, she ‘dives’ into the hacked body of the Puppet Master and they swap places, lying ‘face to face’ (figure 5). He expresses his wishes for them to merge, explaining, “we are more alike than you realise. We resemble each other’s essence, mirror images of one another’s psyche” (Ghost, op cit.). Earlier shots reinforce this connection between the two, showing Kusanagi’s reflection placed next to the ghost-hacked man, and again overlaid with an image of the Puppet Master (figure 6).

Different schools of Gnosticism give varying accounts of Christ (Groothius, 1989), but overall he is diverted away from the orthodox view as Yaweh’s son, instead coming from a higher metaphysical realm in order to ignite ‘gnosis’ or inner knowledge of the Divine. The Puppet Master states that he was born in the “sea of information” (Ghost, op cit.) and is “connected to a vast network that has been beyond your reach and experience. To humans it is like staring at the sun, a blinding brightness that conceals a source of great power” (Ghost, ibid.).

Leading up to the merge, the Puppet Master orates a speech with strong spiritual connotations, exclaiming that “[t]he time has come to cast aside these bonds, and to elevate our consciousness to a higher plane […] It is time to become a part of all things” (Ghost, op cit.). To the Gnostics, acquisition of gnosis is crucial to achieve salvation, return back to the spiritual source (Flannery-Dailey & Wagner, 2016) and fuse with the Divine absolute (Irving, op cit.). Suspense in the scene grows and as the moment of merge draws near, we see from Kusanagi’s point of view a bright, white light emanating from the ceiling and white feathers drifting towards her. At the moment of climax and merge, an angelic figure descends upon her (figure 7), and both cybernetic bodies are shot and destroyed by snipers from Section 6.

Kusanagi awakens to yet another reflection of herself in a mirror. Regenerated in a cybernetic body with a child’s form, she now embodies the ‘androgynous light’ described in the Pistis Sophia (op cit.). Batou asks if the Puppet Master is still with her. Recounting the Biblical passage they heard earlier, she provides context with the preceding passage from 1 Corinthians 13:11: “When I was a child, my speech, thinking and feelings were all those of a child. Now that I am a man I have no more use for childish ways”(The New Testament, cited in Ghost, op cit.). Kusanagi is now no longer the person she was, but someone or something else entirely, explaining: “I am now neither the woman who was known as the major, or the program called the Puppet Master” (Ghost, ibid.). In the final scene, looking satisfied and contemplating where she as a ‘newborn’ will go from here, she tells herself, “[t]he net is vast and infinite” (Ghost, ibid.). For Motoko Kusanagi, gnosis has been achieved.

Subversion of Christianity

Gnosticism is clearly based on a dualism which views spirit as wholly “good and desirable; matter […] evil and detestable” (Groothius, op cit.). This, as has been revealed, echoes the erasure of embodiment found within transhumanism (Hayles, op cit.) and the dismissal of the body common in cyberpunk (McCarron, op cit.). Acclaimed scholar of Gnosticism Hans Jonas (Jonas, 1967) states that its philosophy operates on a “dialectic of, or strife between, opposites or contraries”. Jonas has identified the necessity of reversals within Gnosticism as being of prime importance due to its deeply oppositional nature. This has led to various reversals of many traditional figures in Christianity, as in the Gnostic rendering of Jesus Christ. Barkman (2010) has similarly noted the common occurrence of subverting Christian imagery and themes within Japanese animé, with the tendency to portray it in a pluralistic way.

Ghost’s use of 1 Corinthians 13:11-12 is evidence of this mechanism of reversals. Rather than expressing the Christian view of an individual soul or unique identity, it is instead used to further the concept that spiritual realisation can only be achieved through transcendence or gnosis, and by merging with a higher consciousness outside the self. Barkman (ibid) interprets this as the furthering of a Buddhist spiritual framework, but parallels with Gnostic themes are evident as well. Kusanagi’s self-actualisation is achieved through accepting herself as a continuously changing being and becoming part of ‘all things’ which are also in eternal change. Her ‘childish ways’ were the mistake of believing she possessed an unchanging, individual soul, a concept clearly not cohesive with the Gnostic notion of being mere fragments of the Divine. While Kusanagi appears to have attained a sense of contentment with her identity at the end of Ghost, it is only through the destruction of her material body and the transmutation of her old self that this resolution is made possible.

Bringing the Ghost back to its Shell

Ghost’s attempts to use Gnostic transcendence as an anti-anxiolytic for Kusanagi’s existential crisis presumes that a Gnostic account of the human spirit is one which we should embrace and likewise, that the transhumanist singularity is a worthy goal to strive toward. However, there are further complications in Ghost’s presentation of the relationship between body and ghost. Although Kusanagi’s transformative experience involves her physical body being destroyed, there is one element which is easy to overlook on a first viewing of Ghost. While the Section 6 snipers aim at Kusanagi, Batou is shown to protect her head (figure 8). Her head, containing her cyber-brain and ghost, is then transferred onto the cybernetic child’s body. This implies that there is a link between body and ghost which is necessary for Kusanagi’s continued existence. Notably, the same implication crops up in Patlabor: The Movie (1988) – another of Oshii’s works. A mecha body-suit used as a military weapon gains sentience and goes rogue, and the only way to stop it is by destroying the power source inside its head. Interestingly, Biblical passages are also prevalent in Patlabor. Furthermore, that Kusanagi’s familiarity with the Puppet Master’s cybernetic body serves as the catalyst for her existential uncertainty, extra weight is given to the necessity of embodiment for human identity. Thus, despite the notion in transhumanism and cyberpunk that we can easily dismiss or replace the body, enmeshed within Ghost’s dualistic narrative is also the indication that perhaps we cannot.

Pugh argues that the transhumanist view of the brain as analogous to a computer is in fact an article of faith which disregards the complexity of mind-body interaction, forming the foundation of human experience. He suggests that we should consider ourselves in terms of ‘bodymind’ (Pugh, op cit. p.6) reminding us that language formation relies on spatial orientation and perceptions, gestures and expressions create inner worlds of meaning, and signification and symbols create cultures. Even the formation of memory occurs through the retrieval of patterns stored throughout the body. In Ghost, then, the concept of equating identity with memory, particularly as an informational pattern sourced and manipulatable only through the mind, is cast into doubt.

Conclusion

Relationships between mind, body, soul and human identity are explored in Mamoru Oshii’s Ghost in the Shell through its engagement with transhumanist themes. The film’s superficial setting reflects transhumanism’s claims of operating within a paradigm of secular, scientific materialism, and a deconstructionist, non-dualistic view of the human relationship to the machine. However, under deeper philosophical analysis, an informational dualism and reconstruction of oppositions emerges, which quickly lends itself to being interpreted under a religious framework. The religiosity of transhumanism has been recognised as being primarily Gnostic in nature, and Gnostic themes are identifiable within Ghost. Concepts of life extension, the uploading of consciousness, cybernetic immortality and the human merging with machine reflect within Ghost the transhumanist goal of the singularity, and simultaneously the ultimate Gnostic ideal of spiritual salvation through gnosis.

Rather than being an expression of culturally-specific beliefs, Ghost deals with a universal problem posed by moves towards a transhumanist world. Its underlying Gnostic premise presumes a conception of human identity which is not solidified, and although Kusanagi’s transmogrification is depicted as a resolution, elements which undermine Ghost’s dualism throws this entire premise onto shaky foundations. In the desubstantialisation of the self, the death of God and the erasure of embodied identity, there remain unanswered questions about how to define the human experience. In its discarding of a human personhood which is not equatable to that of a machine, or merely a fragment of a greater spiritual source, Ghost fails to solve the problem of differentiating the human from the machine, in a world where the machine is increasingly impacting on the human. The historically insoluble problem of properly defining the human being thus feels no closer to being answered by Ghost. Thus, despite transhumanist promises of biological and spiritual liberation, Ghost makes it clear that neither transhumanism nor Gnosticism can offer us solace about understanding just exactly where the machine ends, and the ghost begins.

Read Part I: Shells, Ghosts & The God Left Out of the Machine: A Literature Review.

Bibliography

Barkman, A. (2010) Anime, manga and Christianity: A comprehensive analysis. Journal for the Study of Religions and Ideologies, 9(27), pp.25-45.

Barrett, W. (1986) Death of the soul: From Descartes to the computer. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bartlett, R. (2008) The Way of the Crucible. Lulu.com.

Bittarello, M.B. (2008) Shifting realities? Changing concepts of religion and the body in popular culture and Neopaganism. Journal of Contemporary Religion. 23(2). p. 215-232.

Bostrom, N. (2005) A history of transhumanist thought. Journal of evolution and technology. 14(1). p. 1-25.

Brazal, A.M. (2014) A cyborg spirituality and its theo-anthropological foundation. In Feminist Cyberethics in Asia (pp. 199-219). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Coeckelbergh, M. (2010) The spirit in the network: models for spirituality in a technological culture. Zygon®, 45(4), pp.957-978.

Conner, M. (2014) The Spiritual Meaning Behind the Story of Sophia. [Online] Available at:

https://thegodabovegod.com/spiritual-meaning-behind-story-sophia [Accessed: 31 March 2019]

Conner, M. (2016) The Pagan Origins of the Gnostic Sophia. [Online] Available at:

https://thegodabovegod.com/pagan-origins-gnostic-sophia [Accessed: 31 March 2019]

Flannery-Dailey, F. and Wagner, R.L. (2016) Wake up! Gnosticism and Buddhism in the Matrix. Journal of Religion & Film, 5(2), p.4.

Fukuyama, F. (2004) World’s Most Dangerous Ideas: Transhumanism. Foreign Policy. 144. pp. 42-43).

Gaia, (2015) The World’s Soul is a Woman – The Gnostic Myth of Sophia. [Online] Available at:

https://www.gaia.com/article/worlds-soul-woman-gnostic-myth-sophia [Accessed: 31 March 2019]

Ghost in the Shell (1995) [film]. Directed by Mamoru Oshii. Japan, United Kingdom: Production I.G, Bandai Visual, Manga Entertainment.

Gilbert, R.A. ed. (1987) Hermetic Papers of AE Waite: The Unknown Writings of a Modern Mystic. Aquarian Press.

Groothuis, D. (1989) Gnosticism and the Gnostic Jesus. Journal, Summer, 21, p.22.

Haney, W.S. (2006) Cyberculture, Cyborgs and Science Fiction: Consciousness and the Posthuman. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

Haraway, D. (2006) A cyborg manifesto: Science, technology, and socialist-feminism in the late 20th century. In The international handbook of virtual learning environments (pp. 117-158). Dordrecht: Springer.

Hayles, N.K. (2008) How we became posthuman: Virtual bodies in cybernetics, literature, and informatics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Holland, S. (1995) Descartes goes to Hollywood: Mind, body and gender in contemporary cyborg cinema. In: Featherstone, M. and Burrows, R. (eds). Cyberspace/cyberbodies/cyberpunk: Cultures of technological embodiment. London: Sage.

Irving, D.N. (2006) Gnosticism, the Heretical Gnostic Writings, and ‘Judas’. [Online] Available at:

http://www.lifeissues.net/writers/irv/irv_121gnosticism1.html [Accessed: 31 March 2019]

Jacobs, C. (2018) How Ghost in the Shell (1995) challenges the immortality of Plato’s Soul. [Online] Available at:

https://www.academia.edu/30331563/How_Ghost_in_the_Shell_1995_Challenges_the_Immortality_of_Platos_Soul [Accessed: 19 March 2019]

Jonas. H. (1967) ‘Gnosticism’, in Edwards, P. (ed.) The Encyclopedia of Philosophy. New York:

Macmillan. pp. 3-336.

Kitano, N. (2007) Animism, Rinri, Modernization; The Base of Japanese Robotics. In ICRA. 7 p. 10-14.

Kraftchick, S.J. (2015) Bodies, selves, and human identity: A Conversation Between Transhumanism and the Apostle Paul. Theology Today, 72(1), pp.47-69.

Kurzweil, R. (2010) The Singularity is Near. London: Gerald Duckworth & Co.

Matthews, J. (2005) Animé and the Acceptance of Robotics in Japan: A Symbiotic Relationship.

Mead, G. R. S. (2019) Pistis Sophia. Artemide Libri.

Moravec, H. (1988). Mind children: The future of robot and human intelligence. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

McCarron, K. (1995) Corpses, Animals, Machines and Mannequins: The Body and Cyberpunk. In: Featherstone, M. and Burrows, R. (eds). Cyberspace/cyberbodies/cyberpunk: Cultures of technological embodiment. London: Sage.

Parrott, D. M. (1977) Eugnostos the Blessed (III, 3 and V, 1) and The Sophia of Jesus Christ (III, 4 and BG 8502, 3). The Nag Hammadi Library in English, ed. JM Robinson, Leiden, pp.206-228.

Patlabor: The Movie (1989) [film]. Directed by Mamoru Oshii. Japan: Production I.G. Tatsunoko, Studio Deen.

Pugh, J.C. (2017) The Disappearing Human: Gnostic Dreams in a Transhumanist World. Religions. 8(5). p.81.

Puntillo, J. (2014) Self-Awareness in the Conscious Subject: Cyborg Anxieties in Mamoru Oshii’s Ghost in the Shell.

Pyle, F. (2001) Making Cyborgs, Making Humans: Of Terminators and Blade Runners. The Cybercultures Reader. London: Routledge.

Richardson, K. (2016) Technological animism: The uncanny personhood of humanoid machines. Social Analysis, 60(1), pp.110-128.

Schodt, F.L. (1998) BEING Digital. Manga Max. 1(1). p. 18-23.

Tibaldeo, R.F. (2012) Hans Jonas’‘Gnosticism and modern nihilism’, and Ludwig von Bertalanffy. Philosophy & Social Criticism, 38(3), pp.289-311.

Young, J. (2003) The Death of God and The Meaning of Life. New York: Routledge